The day I finally got the chance to cook on the reproduction earth oven was so exciting. I spent most of the morning assisting with transecting and then I got to peel off from the group a little early with one of the other students to go collect wood and set up my fire for cooking. Before I get into the actual events of the day though, I want to go through some of the actual cooking techniques that one can utilize when one can cook on an open fire and how I used this background knowledge on the earth oven.

The important part of the oven was the layer of rocks themselves rather than the fire. Limestone, once heated, holds onto the heat of the fire and serves as a solid cooking surface that food could be spread across. This allows for a consistent cooking time and for the surface area of the oven to be completely covered in food thus maximizing the amount of people that can be fed at one time. As the fire dies the star of the show: charcoal, becomes the most important tool. Raw food should never be cooked in an open flame. Honestly I think that no food should be cooked in an open flame but that’s just a personal preference, I know all those who enjoy burnt marshmallows would disagree with me. Charcoal smolders for a long period of time and when cooking meat, bread, or vegetables, it can be packed around cooking vessels to create an oven with a 360 degree heat source.

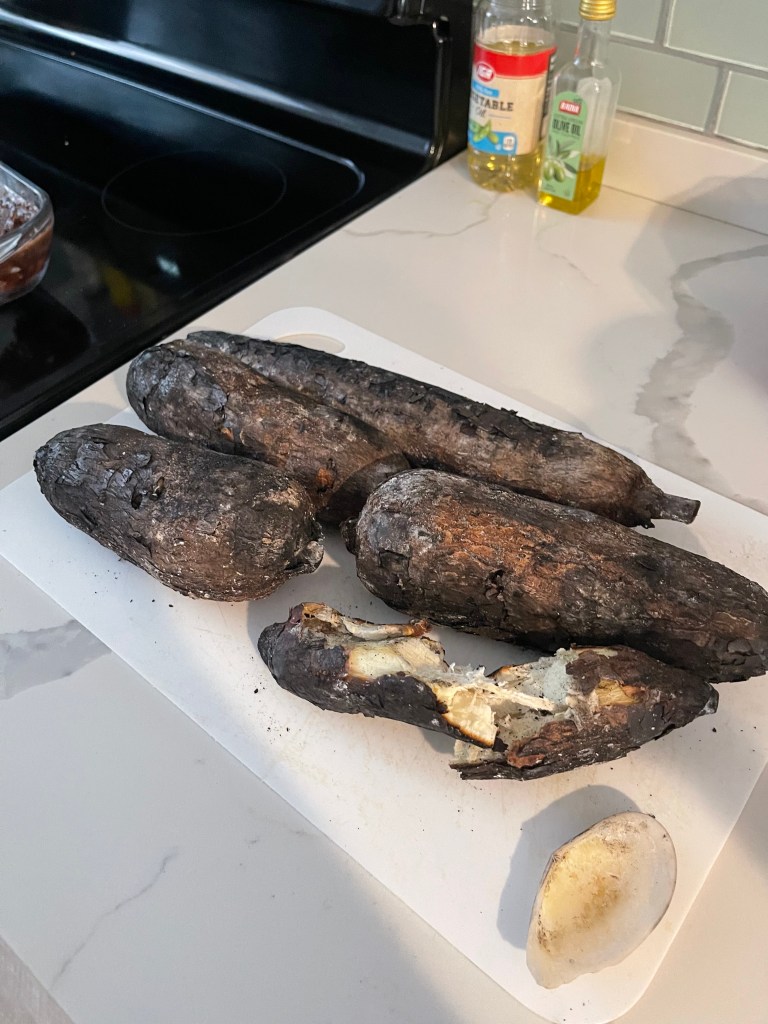

So now let’s get back to the oven. Having done open fire cooking before this experiment, I knew that taking raw tubers like cassava and immediately sticking them in the middle of a fire would completely ruin them as they were burnt beyond belief and would cook them inconsistently even if they were to survive being thrown into the flames. Instead we waited for the fire to burn down from a raging inferno to a collection of smoldering charcoal piles and then placed four cassava tubers around the perimeter of the fire to roast. I attempted to bury one in the fire pit and pack charcoal on top of the tuber, just to see what would happen, but the heat from the rocks was so high, and I was doing this with only a pair of leather gloves and a stick that I eventually gave up and simply made a nest in the coals for one of the tubers.

I watched the cassava as they roasted for around 7-10 minutes on each side, rotating them until they had a lovely roasted smell, and they were slightly soft to the touch.

Then we opened one of them and took a taste. They were surprisingly delicious and completely cooked all the way through! We ended up taking the rest of the cassava home where I turned them into a very anachronistic soup and fed everyone.

While I had a lot of fun cooking the tubers on the oven, and they ended up being absolutely delicious, I feel that there is still far more to be learned from cooking with this method. I plan on continuing my experiments and hopefully recreating more Taino foodways soon. I’d like to see how the temperature is maintained by the rocks and how hot it truly gets. There’s still so much more I have questions about and I feel that this immersive experience is a gateway to further understanding of Indigenous feasting methods throughout the Caribbean.

Leave a comment